Today, we’re going to dive into why you don’t need a fine motor journal and what you can do instead.

We will discuss these three topics:

- developmental stages of writing

- Correct letter formation

- Real opportunities to develop fine motor skills

Also, I’ll answer some of your burning questions at the end of this post, Keep reading!

What is a fine motor journal?

A fine motor journal is essentially a notebook that some teachers use to track their students’ fine motor skill development, using tools like stickers, tape, and tear-off paper.

Honestly, when fine motor journals first appeared in early childhood education a few years ago, every fiber of my being screamed, “No, no, no!”

I mean, since when did fine motor skills and occupational therapy techniques take precedence over child development? Who’s steering the ship?

The bottom line is: Fine motor journaling is a handwriting fad, not a best practice. They are artificial and not a real way to develop these skills. My motto is, “Flat is boring, 3D is fun” and the fine motor journal is about being as flat as possible.

Handwriting and Writing

So, let’s start with the developmental stages of writing. Here’s the thing: There’s a huge difference between handwriting and writing – They are different!

handwriting Form the letters of the alphabet correctly from top to bottom. Writing is putting your thoughts and ideas down on paper.

The only prerequisite for children to actually draw or write is that they have access to paper and writing tools like crayons and pencils. period. period.

In her book, Already readyAuthor Katie Wood Ray says young children are ready to write down their thoughts for real reasons. Why do we make them wait?

This is neglecting the growth of children. It’s like teaching a child to recognize uppercase letters first, then lowercase letters, and then the sounds of the letters. Young children’s brains don’t work in a linear fashion.

To quote a passage from my book: Smart Teaching: Literacy Strategies for Early Childhood Teachers”, “When we don’t teach children how to learn, we set them up for failure.

Writing stage: 2-3 years old

Children’s stages of writing development vary widely, so a one-size-fits-all approach may not be effective. Some children may not be ready for the activities in the fine motor journal, while others may find the activities too easy and unchallenging.

Here is a brief introduction to the typical developmental stages of writing in preschoolers ages 3-5:

Graffiti (2-3 years old)

Make random marks and lines without any specific shape or form. A child may scribble on the paper in a left-to-right motion or randomly—think tornado writing.

This stage represents the child’s early attempts to communicate through writing.

Controlled graffiti (3-4 years old)

At this stage, graffiti becomes more controlled. Your child may start drawing zigzag lines or circles to imitate writing.

Children begin to understand that writing is a form of communication. They may tell stories about their graffiti, showing the beginnings of narrative skills.

Mock letter (3-4 years old)

The child will produce letter-like forms that resemble actual letters, but are not yet actual letters. These mock letters often consist of familiar shapes, such as circles and lines.

Children recognize that letters have different shapes and use these shapes when writing at this stage. They begin to understand that letters are part of the written word.

Writing stage: 4-5 years old

Letter string (4-5 years old)

Random letter strings or letter-like shapes. Children often string together a series of letters with no spacing and little regard for the actual individual words.

Children are experimenting with letters and beginning to understand that letters can form words. This stage is critical for developing letter recognition and familiarity with the alphabet.

Transitional Writing (Ages 4-5)

Your child begins to write letters that are easier to identify and may try to write familiar words.

This stage shows that children are developing an understanding of the relationship between sounds and letters (phonemic awareness). They begin to realize that writing represents speaking.

Eventually, you’ll start to see regular writing Children 5 years and older.

Correct letter formation

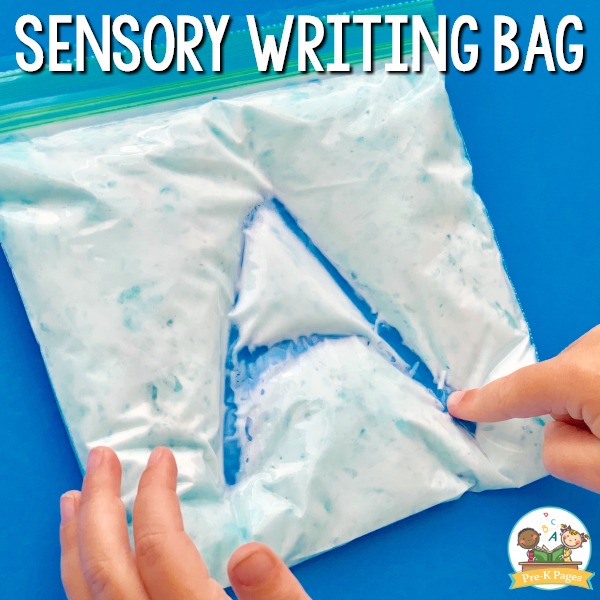

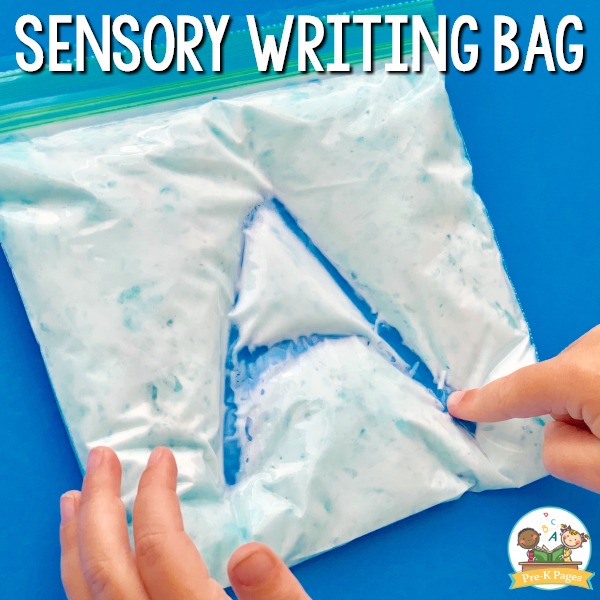

Yes, forming the letters of the alphabet correctly is important, but this can be accomplished through a variety of activities that don’t necessarily require fine motor journaling. For example, practicing writing letters in sand or shaving cream works just as well.

I’ve heard the argument: “How are they going to learn correct letter formation if I don’t use a fine motor journal?” What’s the answer? Through daily modeling and reinforcement!

Modeling in your morning message is key. Reinforce through letters forming songs.

I like the alphabet song heidi songs. These songs teach uppercase, lowercase, and letter sounds simultaneously. You’d be surprised how many students will start singing these songs as they write.

Inject authentic writing opportunities into your classroom. Carry paper and scrapbooks with you block and dramatic performance center. Encourage writing/drawing observations and data collection in the Science Center. Of course, there are many ways to support your writing and/or writing at the Art Center.

For example, when children are “writing” instructions in a drama play center, you wouldn’t stop them because they haven’t learned to write the letters correctly yet, right? That’s ridiculous!

Realistic fine motor activities

Finally, let’s talk about real opportunities to develop fine motor skills. In addition to fine motor journals, there are countless ways your students can use stickers, hole punches, scissors, or tear-off tape in the classroom.

Look at your schedule and assess all real opportunities for your child to develop fine motor skills:

- play dough

- sensory bin

- punching machine

- Manipulate puzzle pieces

- beads

- squeeze liquid glue

- …and even potato heads

Activities such as Write with sand or shaving cream works just as well.

These activities not only help develop fine motor skills but also provide children with a more meaningful and engaging experience. These are more developmentally appropriate than flat fine motor diaries. We want young children to learn through play and hands-on experience because research shows this is how they learn best.

Questions about not using a fine motor journal

Now, let’s answer some of your biggest questions!

“They can freely write or draw in the writing center, so a fine motor journal can’t hurt, right?”

News flash! A little artificial stuff won’t do. We should avoid activities that waste valuable class time. Instead, we should focus on more valuable real-world learning opportunities.

“How will I track my students’ fine motor progress if I don’t use a fine motor journal?”

That’s it student portfolio is for. You can use envelopes to record tearing and cutting tips. Simply place the shredded paper or cut-out sample into an envelope, label it with your child’s name and date, and place it in their folder.

“I keep fine motor journals because my kids love them.”

Of course, kids love candy and soda, too. Just because they like it doesn’t mean it’s good for them. If you asked them if they would like to keep a fine motor journal or play in a sensory bin, which one do you think they would choose?

“How are they going to be ready for kindergarten if I don’t keep a fine motor journal?”

If we had to rank the requirements for kindergarten teachers on the first day of school, number one would be to sit and listen to a story, number two would be to follow instructions. Course fine motor skills yes Important, but they’re not that high on the list.

As the saying goes: “You must have Maslow before you can bloom!” Let’s not lose sight of the children in front of us and their current needs.

There are many alternative ways to develop fine motor skills that may be more effective and engaging than fine motor journaling. So don’t feel pressured into using a fine motor journal and focus on the child’s development first.